Have you ever applied Dermabond to a simple laceration in your ED, and had the patient react like this:

“Really? You are just using super glue? I could have bought that at a hardware store and done that myself.”

Think for a moment. How would you respond to a comment like that?

I had an interaction like this not too long ago. Though the patient was ultimately amicable and appreciative for my services, I came to realize that I didn’t really have a great answer for my patient as to why this particular product in my hands was better than Krazy glue from Ace Hardware applied by himself in front of his bathroom mirror. This got me thinking about the topic, and about my limited knowledge of tissue adhesives as a medical provider. It also got me reading about the specific merits of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (Dermabond) and other commercially available tissue adhesive glues for medical use.

Biochemical structure of various cyanoacrylate glues. Modified from the review by Davis KP and Derlet RW.

Biochemical structure of various cyanoacrylate glues. Modified from the review by Davis KP and Derlet RW.In my search, I found some of the answers I was looking for, as well as some recently published interesting case reports regarding tissue adhesive glue use that help to illustrate the point. The goal of this brief post is to give you a little food for thought regarding tissue adhesives that may help arm you better for this discussion with your patient. Without further ado, I present three things you didn’t know about skin glue:

#1: Gluing skin is not totally harmless. You can get burned!

A full thickness burn from cyanoacrylate glue. Image as published in the case report by Clarke, TFE in the Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive, and Aesthetic Surgery.

A full thickness burn from cyanoacrylate glue. Image as published in the case report by Clarke, TFE in the Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive, and Aesthetic Surgery.This image is the leg of a 2-year-old boy who sustained a full thickness burn when he applied an over-the- counter cyanoacrylate glue (akin to Krazy Glue) to his leg while wearing cotton pajamas. The burn depth and area was significant enough as to require a skin graft! A link to the details of this interesting case report is found here.

This is an uncommon outcome of applying cyanoacrylate glue to your skin, but it does illustrate an important point. When cyanoacrylate glues are placed in contact with cotton or other fabrics, it can lead to a rapid exothermic reaction which can cause burns. This is is felt to be less of a problem with medically produced tissue adhesive glues such as 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate. These glues have longer alkyl chains than over the counter glue for non-medical use (remember the figure at the top of this post that you didn’t quite understand why I included? That’s why.). Thus, they polymerize more slowly and release less heat.

#2: It is safer to eat dermabond than crazy glue.

Probably the most interesting recent novel use of Dermabond was published last year in the Journal of Emergency Medicine as a case report.

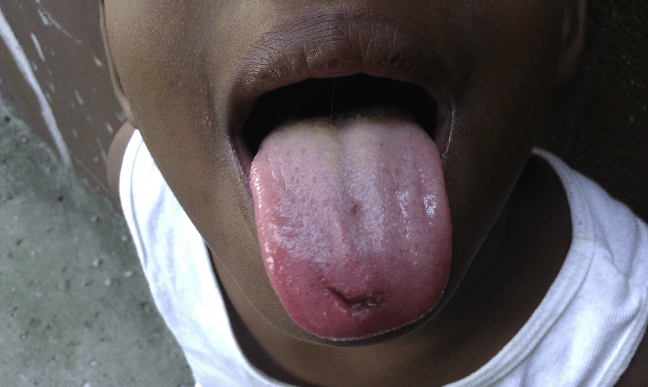

Tongue laceration considered for repair with 2-octyl cyanoacrylate. Image from the case report by Kazzi MG and Silverberg M.

Tongue laceration considered for repair with 2-octyl cyanoacrylate. Image from the case report by Kazzi MG and Silverberg M.The case describes a 7-year-old-boy who had a laceration of his tongue. The parent of the child refused other methods of closure, leaving tissue adhesive glue as the only option for primary repair.

Appropriately, the physician caring for the patient wanted to make sure there was no chemical hazard related to swallowing 2-octyl cyanoacrylate before trying it. As it turns out, the earliest generations of medical tissue adhesives, introduced in the 1950s, actually did have some cell toxicity (in the lab setting). But newer generations of tissue adhesives like 2-octyl cyanoacrylate have longer alkyl chains (I know, I know…again with the long alkyl chains), which effectively means they degrade slowly and this limits exposure of the patient to by-products. So…safe if swallowed.*

(*There is a theoretical risk of bowel injury if the glue hardens in such a way as to form a sharp point when swallowed, but this has never actually been reported.)

Generally, we think of tissue adhesives as not being the best choice for “wet areas,” like intraoral lacerations. If you read the package insert for Dermabond by the manufacturers, it is specifically stated that it is not approved for use on mucosal surfaces. So, repairing a tongue would be considered an off-label use. But, there are other reports in the literature of the use of tissue adhesive glue for cleft palate repair and dental indications, thus there is a precedent.

So in this case, the physicians repaired the tongue using dermabond. I’ll let you refer to the actual case report for details of the technique, but take a look at the final outcome:

Outcome at 14 days after the use of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate to repair a tongue laceration. Image from the case report by Kazzi MG and Silverberg M.

Outcome at 14 days after the use of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate to repair a tongue laceration. Image from the case report by Kazzi MG and Silverberg M.#3: It is not “just” superglue. It is antimicrobial.

An interesting property that is common to all cyanoacrylate glues is a bacteriostatic (and possibly bactericidal) effect. Many very smart biochemists have done excellent work trying to figure out what the exact mechanism(s) of action is/are, but it is still not totally clear.

What we do know is that the antimicrobial effect is stronger against gram-positive than gram-negative organisms; that the anti-microbial effect seems to be at least in part be due to the physical barrier that the polymerized glue creates; and that if the glue is compromised or cracked, the anti-microbial effect is diminished.

Over the counter cyanoacrylate glues tend to be more brittle and apt to crack compared with medically produced ones, which are made intentionally more flexible to accommodate the dynamic movements of the skin. (Once again, this has something to do with those long alkyl chains.) Thus, further argument for the use of medically-approved tissue adhesive glue compared with hardware store Krazy Glue: while all the cyanoacrylates are antimicrobial, medical glue is perhaps more antimicrobial?

Table from the review on cyanoacrylate glue by Davis KP and Derlet RW.

Table from the review on cyanoacrylate glue by Davis KP and Derlet RW.A source for this blog post and an excellent, comprehensive review of cyanoacrylate glues was published last year in Wilderness and Environmental Medicine. The authors compare and contrast medical and non-medical cyanoacrylate glues in incredible detail. Their intent was to determine if non-medical glues have justification for use in austere settings (can you guess what their conclusion was?). I encourage you to read their review. Their discussion is much more detailed than the simple points made in this blog post.

Thanks for reading. I hope that when you are using Dermabond for your next patient with a simple traumatic laceration, you will do so knowing just a little bit more about why you are doing it. If you remember nothing else, remember to tell the patient with confidence: “this specially formulated skin glue has a long alkyl chain.” Trust me, the patient will be impressed.

For a review of the technique of application of tissue adhesive glue, click here.

2 thoughts on “Three things you didn’t know about gluing skin”

Comments are closed.